Addressable LED tech atlas: Part 2

Originally posted on Medium

This is the second of a two part series on technology available around addressable LEDs. Part one, covered different types of LEDs avaliable, microcontrollers and associated libraries.

There are few limits to what you can do with a microcontroller and some LEDs. However, as you grow to a larger scale, or start looking at more complex graphics or interactivity, it becomes easier if we brought more layers of abstraction into play.

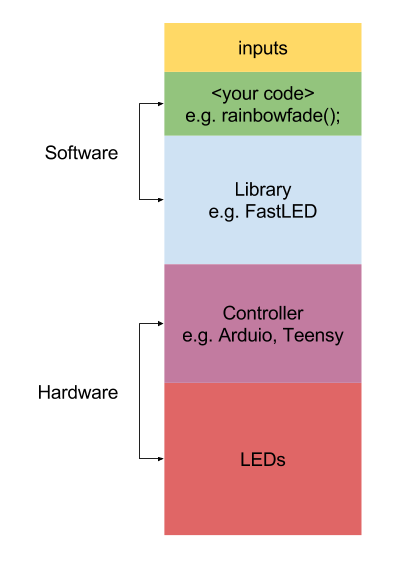

With this, comes a slight paradigm change in how we see your overall system. For smaller, LED projects, we tend to use this abstract view:

Conceptual view of smaller projects

Here, a lot of work goes toward making anything work at all. Thus, more emphasis is placed on libraries and controller boards. The actual animation code often takes less than 50 lines.

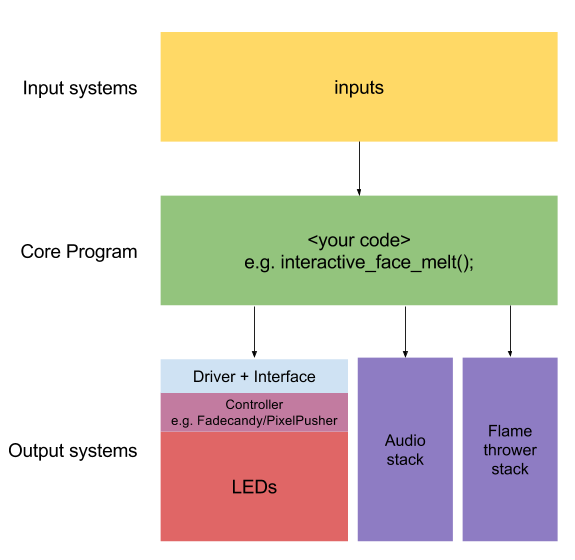

If you are trying to win Burning Man, building an LED installation for a client to help fund a Burning Man project, or one of the more fringe reasons to embark on a large scale LED project, it’s probably more useful to think of your system like this:

Big installation conceptual view

Your unique core program captures the bulk of the complexity in your project. This could be taking a webcam feed, doing some real time video processing, based on sound input, and sending the output to an LED grid and sound system. Or it could be using motion sensing data to light up a stage and trigger flames when certain dance move combos are detected. Your core program will most likely be written in a high level language, such as Python or Processing. This program will likely access the hardware (including LEDs) through a more general interface.

For example, a microcontroller library such as FastLED includes a lot of framework code to make animation and colour related calculations easier. This make sense as your animation code would be running on the same processor as your LED library. However the flip side is that the library can only directly interact with C/C++ code that’s running on the same controller. To interact with another program, running on a different computer, you’d need to get radios, networks, and serial ports involved.

A more generalised LED output stack, as we outline later, will only allow most simple commands, such as specifying that LED 34 is set to the colour that corresponds to the RGB triplet (127, 0, 127). However, this interface can be access by almost any program, often across a network.

–Not sure how this read–

The interface between your program (referred to as “client”) and the LED subsystem (referred to as “server”) is usually the ability to set an LED (addressed by an integer) a certain colour (specified as a RGB triplet). It’s up to the server code to translate that down to well timed signals to the LEDs. The client is responsible for ensuring that the intention of the program is carried out. This means that, among other things, the client need to be aware of the physical geometry of individual LEDs, and their relation to each other.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll discuss three solutions:

Fadecandy

Fadecandy is the brainchild of Micah Elizabeth Scott. She developed the WS2812 only system while working on a Burning Man installation. The system comprise of:

- A custom designed board, based on a Teensy 3.0. It connects to a host system running Linux, OSX or Windows via USB. This is manufactured and sold by Adafruit. Each board can control up to 512 LEDs.

- Custom firmware on the board that improves the range of colours possible from WS2812s, and smoother animations.

- Server software that exposes the LEDs over Open Pixel Control protocol over the network.

The client could run on practically any platform, and written in any language, as long as it can communicate via TCP sockets.

The system is very accessible: each Fadecandy board costs $25, and that gets you up and running. When installed, aRaspberry Pi could be used to the server, controlling upwards of 10 000 LEDs.

LEDscape/RGB-123 Cape

This system is used in many Burning Man installations, and is a combination of several projects. It comes together to expose 1000s of WS2812 LEDs through an Open Pixel Control server, using a BeagleBone Black (BBB) as both the LED controller and server. The components are:

- BeagleBone Black, a computer by BeagleBoard that is similar to, and somewhat more powerful than a Raspberry Pi. Significantly, it contains two Programmable Realtime Units, or PRUs. These can run with enough timing precision to control WS2812b LEDs.

- Ryan O’Hara’s BBB output capes, sold through his RGB-123 shop. These handle level shifting, comes in 24 or 48 strand configurations. Significantly, there is also a version that uses the RS-485 standard to extend the signal via Cat6 cables and RJ45 connectors.

- LEDscape library, originally written by Tremmel Hudson, and forked by Yona Appletree. This contains all the softare, from PRU firmware up to an OPC implementation. This also includes some of the same firmware tweaks that Fadecandy has.

As with the Fadecandy system, there is huge amount of flexibility in terms of what technology the client can use. In fact, LEDscape and Fadecandy could share client code without any modification.

This system has a slightly higher cost of entry, with output capes costing from $35 upwards, in addition to the cost of a BBB ($55). However, it’s becomes competitive with Fadecandy above a scale of approximately 1500 LEDs.

On a tangent: Open Pixel Control and Processing

This pair of technology is widely used for LED control.

Many large LED projects are written in Processing, a Java based language geared at creative coding. It provides easy access to graphics and input handling, but loses some of Java’s more robust testing/compiling tools.

Open Pixel Control (OPC) protocol is used by various projects as the interface between core program and the LED stack. It’s very easy to implement, and Micah Scott’s Processing client implementation, and her example projects are widely used.

PixelPusher

This is the last of the trio of LED systems this article will discuss. Shockingly, it’s also developed for Burning Man projects, by Christopher Schardt. It differs from LEDscape and Fadecandy by being both a bit more flexible, but also closed source and commercial.

- PixelPusher (v3) controller, is the hardware component. It’s a custom ARM board that can control most types of LEDs, including all four types covered in Part 1 of the article. Each unit can control 8 strands of LEDs, and connects to a network via a RJ45 socket.

- The PixelPusher protocol, which allows for easier configuration of multiple PixelPushers as part of the same installation. The vendor also provides tools to bridge control across to DMX, the dominant system for professional theater and stage lighting. The vendor provides a Processing library for client code.

- If you don’t want to write a client program, there is L.E.D. Lab, an iPad App that acts as a default client for the system. The app includes a selection of built-in effects.

The cost of entry for the system is similar to that of LEDscape, with each PixelPusher unit costing $120. But, at 5000+ LEDs scale, LEDscape may be cheaper.